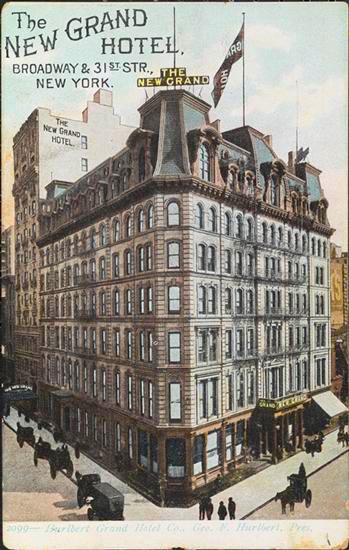

It happened on Broadway and 31st Street in room 84 of the Grand Hotel, in the middle of the Tenderloin—Gilded Age New York's vast vice playground of brothels, dance halls, theaters, and gambling dens.

After knocking on the door several times on the morning of August 16, 1898, a chambermaid entered the room and found the corpse of a pretty young woman, her head in a pool of blood and her clothed body spread out on the floor.

The stylishly dressed woman "had been bludgeoned with a lead pipe to the skull, her neck was broken, and one of her earlobes was torn by the violent removal of an earring," wrote John Oller in Rogues' Gallery: The Birth of Modern Policing and Organized Crime in Gilded Age New York.

"Her clothing was undisturbed, the bed linens fresh and unmussed," wrote Oller. "On a table in the center of the room stood an empty champagne bottle and two glasses."

Police in the Tenderloin were used to gruesome crime scenes, and they were summoned to the hotel to piece together evidence.

The details were intriguing. Though the woman had signed into the hotel as "E. Maxwell and wife, Brooklyn" and was then seen by hotel staff meeting a man in a straw hat, her real identity was Emeline "Dolly" Reynolds, a petite 21-year-old who two years earlier left her well-off parents in Mount Vernon to try to make it as an actress in Manhattan.

Reynolds wasn't getting anywhere as an actress however. For a time she sold books, then met a married man named Maurice Mendham (above). This wealthy stockbroker helped set her up in an apartment on West 58th Street, bought her jewelry, and lived with her "as man and wife," as a prosecutor later put it.

Just as interesting to detectives was the check that fell out of her corset during her on-scene autopsy. "It was made payable to 'Emma Reynolds' in the amount of $13,000," wrote Oller. "Dated August 15, 1898, the previous day, it was drawn on the Garfield National Bank, signed by a 'Dudley Gideon,' and endorsed on the back by 'S.J. Kennedy.'"

Investigators soon learned that Mendham had an alibi; he was in Long Branch at the time. They also discovered that 'Dudley Gideon' didn't exist. But S.J. Kennedy did, and they began taking a closer look at this 32-year-old Staten Island dentist who practiced on West 22nd Street and was introduced to Reynolds by Mendham.

"Reynolds' mother told police that about a week before the murder, Dolly told her that Dr. Kennedy (above) volunteered to put $500 on a horse race for her," according to Strange Company. "She had drawn the money from her bank, and would meet him on the evening of August 15 to deliver what he promised would be a highly profitable investment."

Police arrested Kennedy five hours after Reynolds' body was discovered.

After denying he knew Reynolds, Kennedy then admitted to being her regular dentist, according to Oller, and that he saw her in his office the previous week. He insisted their relationship was professional and that he did not place any bets for her, had never been to the Grand Hotel, and his signature on the $13,000 check was forged.

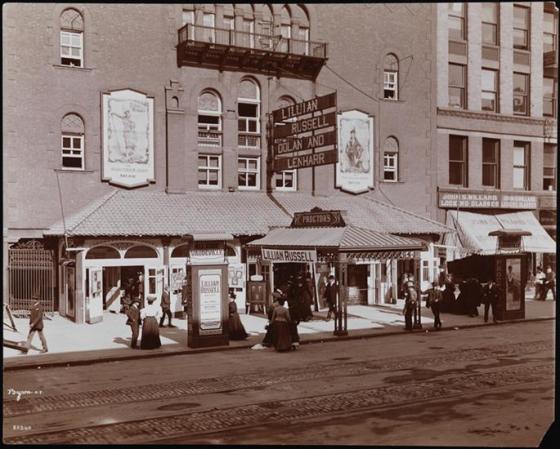

Still, hotel employees ID'd him as the man in the straw hat they saw with Reynolds the day before her body was found. Kennedy also could not explain his whereabouts at the time of the murder, estimated to be at 1 a.m. He thought he'd been to Proctor's Theatre on West 23rd Street (above), but he couldn't recall the name of the play he'd seen, wrote Oller.

Police and prosecutors came up with a theory to connect Kennedy to Reynolds. "According to the theory, Dolly was just one of the 'lambs' that Kennedy, a feeder for a group of confidence men, was tasked with separating from their money," explained Oller. But there were some holes, such as why the check was for $13,000, and why the dentist murdered her so viciously.

The March 1899 trial riveted New York City, and newspapers printed lurid front-page headlines with illustrations of the courtroom. Hotel staff and guests (like Mrs. Logue, above) took the stand; Kennedy did not. The jury quickly convicted Kennedy and sentenced him to die in Sing Sing in the electric chair.

But then, the convicted dentist got a lucky break, when in 1900 the Court of Appeals granted him a new trial due to "hearsay" that was used as evidence in the first trial.

The second time, the jury deadlocked, with 11 voting to acquit. At a third trial, Mendham testified, and "his evasiveness about the extent of his relationship with Dolly Reynolds fed the defense's insinuation that he was somehow behind the murder," wrote Oller.

While crowds sympathetic to Kennedy rallied outside the courtroom, the jury couldn't agree on a verdict once again. The city declined to try the case a fourth time. Kennedy was released from the Tombs and returned to Staten Island to a hero's welcome.

"He resumed his dental practice and lived quietly in New Dorp, dying at age 81 in August 1948, almost 50 years to the day after the murder of his patient Dolly Reynolds," wrote Oller.

[Top image: San Jose Mercury News; second image: MCNY X2011.34.35; third image: New York World; fourth image: The Scrapbook; fifth image: MCNY 93.1.1.15639; sixth image: New York World; seventh image: New York Journal]